So you want to help shift workers feel better—sleep better, be safer, have fewer of the long term chronic health problems that go hand in hand with shift work. How do you do it? Where do you start?

As some of the most circadian-wrecked people around, shift workers have been the topic of no small amount of research. Yet one incontrovertible, “best” strategy has failed to emerge for what shift workers should do. There are plenty of reasons for this, but the short answer is: it’s complicated! There are a lot of possible shift schedules a person can be on, and a lot of variation from person to person in how those shifts will affect them. In this blog post, I’ll try to chip away at the complexity a bit by covering what’s currently known about strategies for shift work, and what shift workers might do in the future.

Rather conveniently, a lot of the ways you try to help shift workers can be framed as a choice between two alternatives. So let’s start with one of the biggest “versus” there is out there.

Homeostat vs Circadian Interventions

There are two main forces that conspire to make a person feel sleepy. One is your sleep hunger, or sleep homeostat—basically, a build up of “need for sleep” that accrues when you’re awake, and drains when you’re asleep.

The other is your body’s circadian clock, which sends an extra strong signal once a day to tell you to go to sleep. These aren’t the only things that make a person sleepy, but they explain a lot of the phenomena we see in shift work contexts. This way of thinking about sleepiness (homeostat plus circadian) is called the “two process model of sleep.”

You could classify the strategies around helping shift workers into two camps, based on which of these two forces—homeostat or circadian— they’re primarily targeting. If you want to have a low sleep homeostat going into the night shift, for instance, you probably want to sleep as close to before your shift as you can. So you might try staying up until 1:00 pm on the day after your shift, building up a ton of sleep pressure, then falling asleep for most of the afternoon and evening, waking up right when it’s time for work. Naps and caffeine would also fall under the header of “mostly targeting the sleep homeostat.”

Targeting the circadian clock, however, means moving your rhythms to promote sleep at a time you actually can sleep. This means phase shifting your clock, which can be achieved by doing the kinds of activities that matter to the clock (getting light exposure, avoiding light, exercise, etc.) at the right times.

These methods aren’t mutually exclusive by default, but they can be in conflict at times. A lot of what decides that is the direction you choose to move your clock in.

Advancing vs delaying the clock

A totally day-adjusted person will probably have their peak fatigue hours occur sometime in the early morning; say, 3:00 am. If they go on a night shift, those peak fatigue hours are happening right in the middle of work hours. (Not exactly ideal). So you could shift their rhythms so that their worst hours no longer happen at 3:00 am.

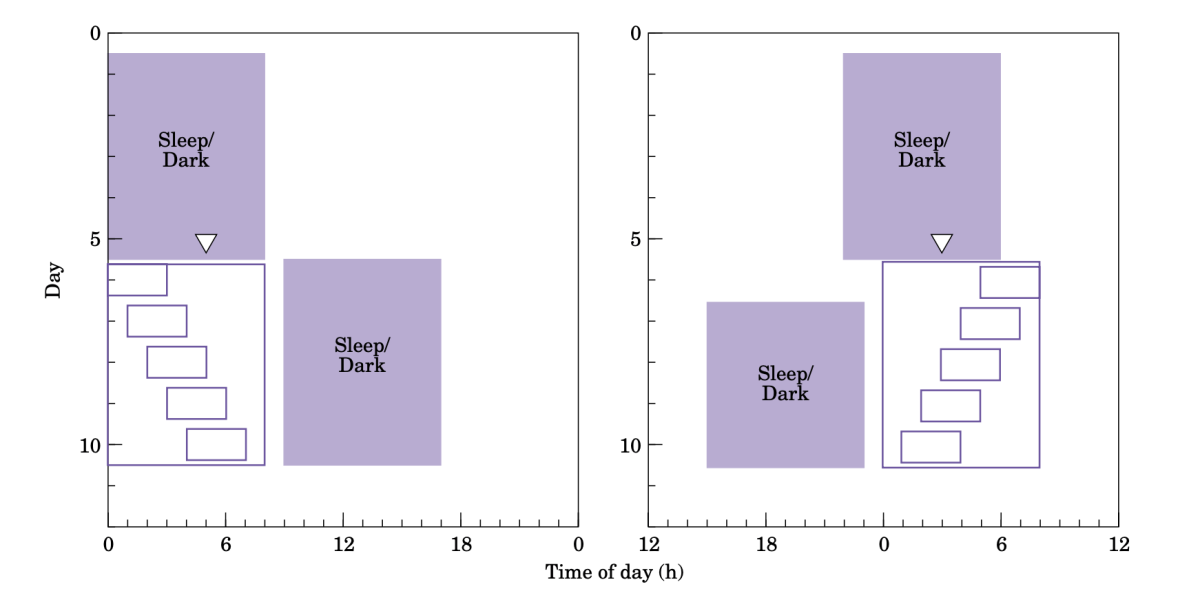

Way #1 to Achieve This: Shift them later, or delay their clock. Move it so they’re feeling the biggest circadian drive to sleep at, say, 9:30 am, after they’re home from work.

Way #2: Shift them earlier, or advance their clock. Move it so they’re feeling the biggest circadian drive to sleep at, say, 5:00 pm, or before they go to work.

Way #1, or delaying the clock, is often called “compromise phase position.” The idea is that it’s a compromise for the night shift life—you’re not totally shifting to a nocturnal schedule, but you are getting the time of day when your clock maximally promotes sleep to be outside your work hours. You can do this by blasting yourself with light in phase delay portion of your body’s daily rhythms, which for a person who’s still pretty adjusted to the day schedule is going to be in the afternoon and evening. Note that this is where we start to conflict a bit with the homeostat-targeting interventions: If you’re keeping yourself in a super bright environment in the hours before your shift, you’re probably not sleeping the whole time you’re at it.

Way #2, or advancing the clock, does not come with the same homeostat conflict. To advance the clock, a person still relatively well-adjusted to a day schedule would want to avoid evening/afternoon light and get tons of it in the morning. A “sleep after 1:00 pm” intervention in which people were also dosed with bright light in the latter part of their shift saw a 3 hour shift in the timing of the circadian rhythm biomarker, dim light melatonin onset (DLMO). In other words, you can target the homeostat right before a shift and promote an earlier phase shift at the same time.

There’s evidence that both strategies can improve upon a baseline of undirected, “do what you want” advice to shift workers. Advancing the clock plays nicely with “sleep before shift” strategies, but you could also take a pre-shift nap, while mostly delaying yourself in the lead up to it. You could also try splitting your sleep—sleeping right after your shift, and then again right beforehand, and using your non-sleep time to steer your clock in one direction or another (though depending on what your personal time zone is, this may be a bit difficult—those hours might be times when you’re more or less insensitive to light).

So how do we begin to choose a strategy to recommend? Well, there’s one missing dimension to all the research touched on so far that we haven’t discussed yet.

Non-shift workers vs. shift workers

All of the shift working studies cited above looked at non-shift workers who were brought into the lab and put on simulated shift work protocols. Typically, being a shift worker was an exclusion criteria for the study: No real shift workers allowed.

There’s a very good reason for this, which is that shift workers have wonky circadian rhythms. You bring shift workers into a lab and look at their dim light melatonin onset timings, and you can see coverage over almost all the 24-hour clock. This means that you wouldn’t expect a nice clean scientific result to come out of putting them all on the same schedule: What’s good for someone would almost certainly be terrible for another. Focusing only on non-night shift workers (who are, it should be said, a good model for “just starting out on the night shift workers”) means you’re able to better parse a signal from the noise.

But it also means that you miss out on a very important piece of information: Namely, that only a tiny fraction of shift workers phase advance themselves in the real world. Many of them don’t follow particularly great strategies, but the ones who are better adapted tend to be very delayed.

This result comes from work in night shift nurses that looked at the different strategies that real nurses employ. In that research, the “most adapted” nurses were the ones who basically did this compromise phase position strategy, where they were very late types on their off days. Nurses who stayed up all night before a shift or napped during the day on their off days tended to be worse adapted— worse mood, increased cardiovascular risk, you name it. Counterintuitively, the least adapted nurses also tended to be older and more experienced on the job.

When you step back and think about shift work in a vacuum, the truly best strategy from a health perspective would probably be for shift workers to shift their lives entirely to align with night work, sleeping during the day even on the days they have off. In that sense, it would be like living in the United States but pretending you worked the same hours as a person living in Tokyo. With good enough blackout curtains and strong enough willpower to ignore the FOMO of diurnal life, you truly could fully adapt to a night-living lifestyle.

A tiny fraction of real shift workers do this. But most don’t, and the vast majority want to sleep at night during the days they’re not working. The better adapted nurses in the Vanderbilt study achieved this by being pretty extreme night owls on their days off. The poorly adapted nurses, the older ones who tended to stay up all night or nap on off days— they might be the ones to benefit most from a phase advancing schedule, which appears to have worse discoverability (nobody really does it in the real world) than the delaying schedules. In other words, if one direction isn’t working—as it appears not to for the ill-adapted shift workers—try going the other way.

Time now for my caveat that this is all, once again, pretty complicated. You can be an extreme night owl on your off days right up until the moment you have to work a 7am to 7pm shift. Your actions during your off days and off hours are constantly shifting your circadian profile, so that the thing that works for you one week might not work for you the next week. None of these studies could look at DLMO changing day-by-day in the real world, because none of them had the ability to track DLMO cheaply and in real-time. What do you want to prioritize—safety on the commute? Safety during shift? Ability to sleep well and feel good? Putting one of these above the other can give you a different answer. It’s a lot.

Enough already! What should I do?

Listen, if there was a one-size-fits-all easy solution to all of this, we wouldn’t have made an app for it. I would just have emailed everyone this blog post and done that thing where you brush your hands together in the international sign of “all done here.”

Here’s one rule-of-thumb, though: If you’re adjusted to a day schedule, and you’ve got a one-off night shift tonight before going back to the day schedule, you’re not going to be able to meaningfully shift your body’s circadian clock in the next 8 hours. You’re going to want to bank as much sleep as you can in the hours leading up to it and be aware of when your peak fatigue hours are going to occur. Our app can help you with that.

For everyone else, this is where our app comes in. Shift builds on this history of research to design plans unique to your body clock. You can choose which ones to try, and give feedback on the ones you like and don’t like. Want to help us move the needle on getting shift workers to a healthier place? Reach out for early access.